For five weeks Kirstin hosted a group of Amnesty International students and we were obliged to play with them.

For five weeks Kirstin hosted a group of Amnesty International students and we were obliged to play with them.

(The family here in Bolgatanga, Ghana)

(The family here in Bolgatanga, Ghana)

(the tree-planting gang in a village higher up than ours)

(the tree-planting gang in a village higher up than ours)

(african elephants)

(suspended canopy walkway)

and now:

THE cyclying tour journal...

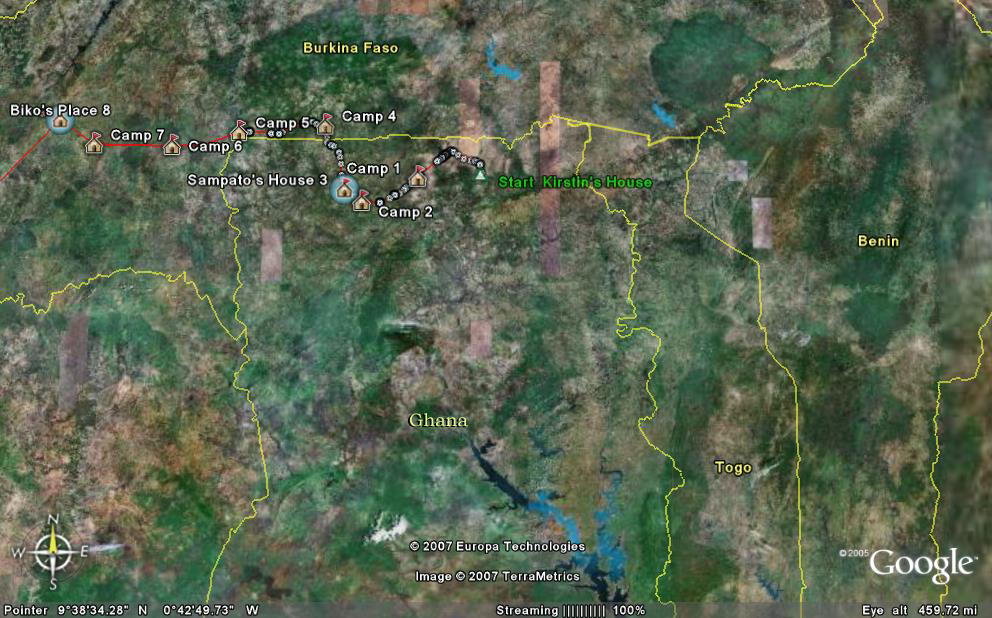

(Right click and "save as" the above image to download the GoogleEarth file)

(Right click and "save as" the above image to download the GoogleEarth file)Bolgatanga (Ghana) – Leo (Burkina Faso)

West Africa is not a particularly popular place among living things whom choose to parade a thriving lifestyle bountiful in extravagance and grandiose reproductive prosperity. No, that attitude is better suited for lands and individuals radiating far away from here –places not dominated by an ever-encroaching Sahara desert. Here people, plants, and all furry or scaly or feathery or slimy little creatures hang on to life by the thinnest of thirsty threads and, I expect, are wondering why they didn’t just decide to go evolve somewhere else for awhile; perhaps somewhere nice and moist and tropical. It’s true that life is everywhere here, but in this post-harmattan/pre-rainy season western part of Africa the land is dry, the roads are long, lonely, unchanging, & dusty, and the air is void of breezes, sounds, and activity…it is into this environment that we begin our bicycle ride: Kirstin on her hand-painted electrical-taped mountain bike and I on a single-speed.

We are starting this ride as three: Kirstin, Me, and Sampato. The first two you know; Sampato is new to this blog. He is, by trade, a motorcycle mechanic. He is, by passion (and by "passion" I mean "hope"), a mango farmer, bee keeper, and cafe proprietor. Motorcycles he fixes, mango trees he is growing, bees he is planning, and cafes he is dreaming. As a friend of Kirstin's she had hoped we would meet him upon our initial arrival here in Northern Ghana. However, when we arrived there we heard of the bad news: he and his wife were caught in a house fire, his wife is okay but Sampato is in a village hospital badly burned while struggling to survive. Wow. A sadness crept over the next few days and we wondered if we would ever meet this quiet friend and, subsequently, benefit from his groovy furniture making skills.

Imagine how surprised I was when, a few days later, I met Sampato, not mummied up in body bandages or glowing, lifeless, and hovering inches above my bed at night as I might only have expected, but on a 100 mile bike ride away from his village standing on Kirstin’s doorstep smiling and greeting us. Er? “Is this the fellow that is supposed to be dying?” I enquire. I was assured by distant burn marks on his arms and legs that he was either 1. a walking ghost or 2. a product of a glorified and badly researched sensational African rumor.

He was alive, in perfect health, and of one of those rare African breeds that’s does (and enjoys) traveling long distances via bicycle.

A few days later he greeted us with a gift of honey from his village. A gallon jug of honey. Delicious, raw, direct-from-the-bee, dark and chunky honey itching to be eaten by the spoonfuls by dripping gooey smiles. When we learned that our ride out of Ghana could be routed through Sampato's honey-saturated village we jumped at the opportunity to have him take us there. And that first bit is what you're about to read.

Looking at the map Sampato’s village (Tarsaw) appears to be about 170 kilometers away on roads marked "secondary roads" & "other roads or tracks or trails." That description leaves a lot to the imagination. Sampato calls these roads "bicycle roads." I think that sounds perfect. And so we begin our ride with a well-equipped guide loaded to the gills with motorcycle parts to bring health to the motorcycles of the needy people of far away lands home to remote villages where nature and the radio still compete for human attention.

The road out of Bolgatanga is a good road. We would find pavement all the way to Sandema about 70 km away. It should be noted: the next two months of this journey we are expecting a lot of savanna and an opportunity to be well acquainted with the sun. Imagine how pleasantly surprised we were to be zipping through a cool, paved, tree-shadowed corridor. Don’t get used to it. Don’t get used to it. Don’t get used to it.

Reaching Sandema the day was growing late so we collected food in town with the plan to pedal on a few more kilometers and then hole up some place in the bush. That someplace turned out to be a farming field attached to a quaint house of a nice gentleman and his family. The food we gathered in town and brought to camp looked real nice…but it wasn't.

The beans were scrumptious but they suggested regurgitation once we realized they housed "beans worms." Had any of the beans wanted to stay down, and we disagreed, we could send the pepper sauce down to renegotiate the deal because it tasted a few weeks past fresh, in the soup swam dead bits of animal bones that we gave to Sampato to consider, and the bagged hibiscus juice for dessert was bloating its bag so urgently that whatever was fermenting inside must have felt that fermenting outside would suit it better. Drinking that would have really sent someone running for a place to be sick. Had there been anyone to return the food to we would have, which there wasn’t, had they been around they wouldn't have taken it back.

Only the fried Yam chips could be eaten but not without a hunger for nutrition.

Aside from discontented stomachs, sleeping was comfortable and starry. Only the women who joined the household around midnight and started up a fight could stir us from our dreamless sleep.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

If it wasn't for the countless NGOs (non-governmental organizations) working in their selfless manner to bring fresh water to the far-out villages of west Africa, not only would people have a considerably more challenging shot at surviving in this dry region, we would warily be filtering water out of disappearing pools of unthinkably murky water. Thankfully (for us, maybe not for the ecosystem grotesquely unbalanced by the unnatural human population) these organizations have erected an army of groundwater pumps coincidently everywhere that we have needed a water bottle filled.

(wow, those little fellers are letting me do it myself!)

From far away we know those sparkling metals and vibrant colors as aluminum pails and the vibrant dresses of the village woman grouped around a single pump balancing these oversized bowls unwaveringly on their heads. They can trek 100 pounds of water along rooted pathways and through winding village alleyways, without faltering, home to wash their family's clothes, cook their family's food, and bath their family's persons. I can't imagine how much work it is to fetch the necessary water because I’ve never had to properly do it –haul it in on my head– and so we roll up on our fancy bicycles and fill comparably half the weight in water in our own the bags. On such occasions, arrival at these hand-pumps there are greetings exchanged while a million small children materialize out of the trees to form a tightly knit circle around us. Enclosed in this nest our bottles are snatched anonymously from our hands like juicy bits of meat, filled, returned by raggedy T-shirts and grinning teeth and typically we are grudgingly freed with a full load of mineral-rich groundwater jiggling in the bags.

Cuisine report:

This morning it was off to a wonderful breakfast of bambara beans and a bowl of porridge served from underneath a non-descript baobab tree. Mmmmm.

Not-Mmmmmmm was Sampato's addiction to coffee and his need to mix the instant stuff in with his mealy porridge. Echhh.

Soon the dirt road turned to alternating double and single track and occasionally a push through a dry river bed. There gets to be a point as the road degrades when tourists, and by extension white people, no longer frequent its passage. At a certain point white people like us are no longer a curiosity but something to be reckoned with. We sat with a chief who asked us for groovy village installments like buildings and well pumps. Hmm, how about a mango? Adults demand our attention for a fleeting greeting or full fledged (non-English) conversation whilst children either appear in masses to quietly gaze at our passing or run away in fits of screaming horror upon seeing my preposterous white face and Kirstin's devilish blond braids.

Fortunately as the road narrows to bike paths so too does man’s influence. The scenery is becoming beautiful. Without enough people to cut them down the trees around here are obliged to grow and reproduce creating diverse arid forests. With these trees come loads of birds singing their songs. But no big wild animals yet.

In Nobalo, a village approaching Sampato’s, he was surrounded by about everyone with a motorcycle. We rolled in early enough, but he was up past midnight fixing everything from carburetors, to tailpipes, to tires, with not much more than a hammer. We slept on the floor of someone’s house and ate wonderfully crafted vegetarian food by special request.

It was with a heavy heart that the town waved him goodbye the next morning in the form of motorbikes yet to be repaired. He would return, he promised, as we puttered away from an adorable town of mango trees and honey bees.

It was with a heavy heart that the town waved him goodbye the next morning in the form of motorbikes yet to be repaired. He would return, he promised, as we puttered away from an adorable town of mango trees and honey bees.Before noon we would arrive in Sampato’s village, Tarsaw, and settle in to his house. Here is a village life that we find endearing but our friend with a nomadic heart finds it a stranglehold on life.

His story (though it seems to change from time-to-time) is something like this. When Sampato was a small boy his Uncle died and, through whatever means that made sense to the elders, his uncle’s wife was passed to him. More of a mother than a wife, and more of an elderly lady than a teenage girl, she kicked over awhile later easing the way for Sampato’s newer wife to climb the wife hierarchy. She was hand picked by the old lady-wife, and was described by Sampato at first as very “hogly”. She came from another village, (something something something) Sampato's village is mad at him and his family for marrying incorrectly, (something something something), the wife’s village is mad at the husbands village and now everybody is in trouble. Life at home is a bummer for awhile, things don’t look so bright for the future, and then through magical means which I never understood, amends are made and everything is okay again. Our friend is still searching for his “chosen wife” and would probably leave everything he has built with wife number two if he found someone better (ie an American, or a rich woman that he could ride bikes around and drink coffee with.)

(Cracking Peanuts)

(Cracking Peanuts)

But still the family isn’t happy and remains together for the sake of tradition and social reasons. Remember the burning of the house? A result of his wife tipping a kerosene lantern over in the bedroom. According to Sampato, his wife is threatening to leave with the children if he can't raise the money to replace the burned away roof. It’s about nine square feet of wood or aluminum covering.

Yikes! If only divorce was always so colorful, eh?

Crazy as a loon the woman may be, but she sure can cook. Another special order vegetarian village cooked meal proves to me that Ghanaian food is fantastic –provided it doesn’t have meat in it –which it nearly always does.

And that's not just me poo-pooing on dead animal food. Meat can be cooked deliciously, I’ve known a few eel rolls in my life that can agree, however Ghanaian meat dishes are dreadful. For whatever reason they choose to chop up meat into its most pathetic cuts, let it sit long enough in the open air for the repulsive flavors to replace the good ones, and then cook it in a stew so these tastes overrule the delectable spices and mashed up veggies of the soup. But not everyone can afford hunks of boiled goat spine in their stew and that's when sun-curled, time roasted, and smashed miniature fish is added for flavoring, nutrient and that fun little crunch of bones, eyeballs and gills. I guess it’s an acquired taste, however, because there isn’t a Ghanaian out there that doesn’t love their goat and fish stew.

We spent two nights in Tarsaw touring the area, meeting the people, eating food, doing laundry, etc. etc. just to prove how boring it really was. But the Mango tree kept me on my toes. Growing in the courtyard of Sampato’s house this giant tree provided shade for the day and pleasantly rustling leaves of the night. However, always there was the restlessness in the background of my mind that I would be struck. “WHAM!” would go the tin roof when a mango crashed down onto it thus jerking me upright from my relaxed position. “FLOPST!” say the mangos when they hit the ground. A whistling and then, “KONK!...Flop” is the sound I wait to hear when one sails out of a tree and bashes me or Kirstin on the head.

We spent two nights in Tarsaw touring the area, meeting the people, eating food, doing laundry, etc. etc. just to prove how boring it really was. But the Mango tree kept me on my toes. Growing in the courtyard of Sampato’s house this giant tree provided shade for the day and pleasantly rustling leaves of the night. However, always there was the restlessness in the background of my mind that I would be struck. “WHAM!” would go the tin roof when a mango crashed down onto it thus jerking me upright from my relaxed position. “FLOPST!” say the mangos when they hit the ground. A whistling and then, “KONK!...Flop” is the sound I wait to hear when one sails out of a tree and bashes me or Kirstin on the head.

Before leaving Tarsaw for Ghana’s border with Burkina Faso our host fulfilled his promise and packed my Camelbak with two liters of the darkest, richest, rawest honey I'll likely ever suck out of a hose. Mmmmm, that will power us far on this journey for sure.

The Border to Bobo-Dioulasso (Burkina Faso)

Cuisine Report:

Crossing the border from the English-colonized Ghana to the French-colonized Burkina Faso was undramatic in all ways except for one: the change of food (ah, and the switch from English to French. That one left me both deaf and dumb). Suddenly in place of street food choices of mammaly beans & rice or nasty fishy beans & rice we had spaghetti, fresh salads, mangos, yoghurt and baguettes to feast on. And feast we did.

(I remember one campsite in particular, I call it Entomology camp. The number of insects scurrying under the leaves was astounding. The diversity in ant types was staggering though everyone else had me running for safety in the tent.)

We made the decision to keep our bikes off the few super highways of west Africa that connect major cities in the best way that single-laned - pot-hole-peppered roads do. Planning to stay away from using these routes wasn’t necessarily because the drivers of them tend swerve away from road blemish and into cyclists, or that they swerve away from other swerving cars and into cyclists, or that they swerve around animals and into cyclists, rather it was the peace and serenity of the clean air and simple village life of the long dirt roads of which these grimy highways have come to replace.

Every day riding these dirt roads through every village feels to us like riding through an endless parade where we are the main attraction on the greatest float amongst the most excitable crowds. Every aware adult in sight of the road (and there are a lot of them) requires a wave and a "Bon jour." Every shopkeeper, every pedestrian carrying on their heads logs, bricks or chickens, every woman pumping water, every circle of outdoor boozers (and there are a lot of them), and every person sitting for no other purpose but to sit (and there are more of them than anyone) requires a wave without which they are offended and will certainly cast a wicked Ju-Ju spell on some of our more critical bicycle components. The waves and the greeting are manageable, even friendly and welcoming the first half of a day; it’s the kids that drive us nuts. It’s the kids that can make a peace-lover turn violently wicked. Like a bear smells honey, and with 100x the ambition of an American child racing for an ice cream truck, the children of the villages come tearing out of their sedentary lives making for the road. From there they choose to either stand on the road's edge screaming and waving like rabid banshees or, if they sense our fear, come chasing after us down the road with sadistic little intentions of fulfilling that same cardinal desire that is quenched when an able-bodied someone with a foot fetish competes in a tickle competition against paraplegics. All the while, and without fail, the children chant their little song of "Tu-Ba-Boo, Tu-Ba-Boo, Tu-Ba-Boo." We assume that means "foreigner," maybe even, "hello foreigner, welcome to our village, so nice of you to roll through," but more likely it's just a way for these rotten little kids to skirt around the imposed social rules of “respect for one’s elders” to taunt faceless foreigners devoid of social status and feeling.

But they're not all little monsters (yes, they are). Village kids living along roads-less-traveled are quiet, polite, and totally fascinated by us and our gadgetry. When we actually stop the float, dismount, and materialize into real people the adults are friendly and the kids form a village-sized circle of curious and unwavering eyes that crowd in close enough to squeeze oranges. And then they just stand there and stare; fascinated by our smallest movements such as drinking water, scratching our heads, or checking the power levels of our soar panels charging an iPod which is transmitting an fm radio station to a radio we have playing an audio book. Kirstin tends to break the spell by asking one of the elders to have the gelatinous human fortification do a song and dance routine until we're ready to leave. That gets them shaking up a bit.

Ooh ooh: Mango consumption has increased heavily since we entered Burkina Faso and its smaller villages. Ghana offers little that resembles an edible mango –more of a pale yellow stringy capsule of goo– but Burkina is swimming in deliciously perfect Mango trees glutton with beautifully perfect mangos and these backwater Burkina villages are absolutely drowning in them. At 20 CFA each, or about $.03, they’ve become quite the bargain and the staple fuel to power our riding.

Today while resting under a tree eating a few of these mangos a strange little fellow walking this long lonely dirt road stops and is offered a drink of water by Kirstin; he returns the favor by offering us small packets of what looked like heroin. We politely refused.

Evening time and riding through the village of Klesso we stopped for rice and stew. A short conversation later a gentleman had invited us to stay the night with him and his family along with the hinted possibility of dinner. We accepted.

A simple and traditional village it was and his, Seidu is his name, house fit in as it circled around a mango tree. Making up the complex were his mama and papa Smurf parents, a kitchen, wood shed, and outdoor shower with walls high enough to cover ones navel. We greeted the elders of the town, were on display for the village children (despite Seedu continually whacking them with sticks and throwing rocks), bathed, rested, and Kirstin conversed in French. After nightfall Seidu had disappeared for some time eventually returning with our choice of dinner being held by the feet: A chicken, small hen, or Guinea Fowl. Groovy but our vegetarian lifestyle scored us a pot of spaghetti noodles (with traces of veggies and seasoning) instead.

(scroll through the panorama above)

Tinkling one house behind us his brother tapped away on a balophone setting the mood. A balophone is much like a xylophone but instead of metal its keys are made of local hardwood and underneath each is a calabash (a gourd) echo chamber. And so to candlelight and local music we feasted on spaghetti and baguettes in a little African village in the middle of nowhere. We were told, too, that sure they have driven through before, but we were the first whiteys to stay in the village.

Oh, and late that night Kirstin rose to use the potty in the bushes about 25ft away, disoriented herself, wandered helplessly through houses for a good 30 minutes looking for us. Finally, surrendering and prepared to curl up snug with some chickens and pass the night warmed by pigs she noted the searching beam of Seidu's flashlight and managed to stumble home without having to resort to the chicken/pig plan.

Seidu and his family represented the amiable hospitality Africa is famous for, it’s a shame he cornered us the next morning as we waited out the rain and repeatedly asks us for the money to rebuild his house. Was it more of an insult to give him only the $2?

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

A week into our trip and we reached our first goal: Bobo-Dioulasso where our American friend Biko put us up for a few days of recuperation with live music, the river, chocolate croissants, wine, and laundry.